Making Precision Oncology A Reality

April 14, 2019By Dr James Creeden, Global Medical Director, Foundation Medicine

The global cancer burden is on the rise. According to the World Health Organisation’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), there were 18.1 million new cancer cases and 9.6 million deaths worldwide in 2018![]() i, up from 14.1 million and 8.2 million respectively in 2012ii. Home to 60 percent of the world’s population, Asia contributed to half of all new cases and deaths in 2018i.

i, up from 14.1 million and 8.2 million respectively in 2012ii. Home to 60 percent of the world’s population, Asia contributed to half of all new cases and deaths in 2018i.

The good news is, rising in tandem are medical advances and innovations that are offering doctors better diagnostics tools and treatment options, and consequently new hope for patients. In particular, the rise of precision medicine and personalisation of cancer care is gaining traction and beginning to show results. Cancer was once broadly categorised by where it is located in the body and often treated uniformly. Now, cancer is better understood by the exact molecular alterations driving it. This means that each tumour, just like each patient, is unique. This translates into the following benefits:

- By identifying the distinct genetic genomic characteristic of each patient’s tumour, physicians are empowered to choose the appropriate targeted therapy, which pinpoint and attack only the cancer cells affected by the known mutations that are promoting the growth of that cancer.

- Such a tailored, high accuracy approach (i.e. precision medicine), minimises side effects and increases efficacy for patients

- Doctors will be able to identify patients who may be candidates for clinical trials, where they can receive the latest precision therapy options, as well as patients who are not likely to respond to any of the available targeted therapies, which allows them to avoid administering futile treatments.

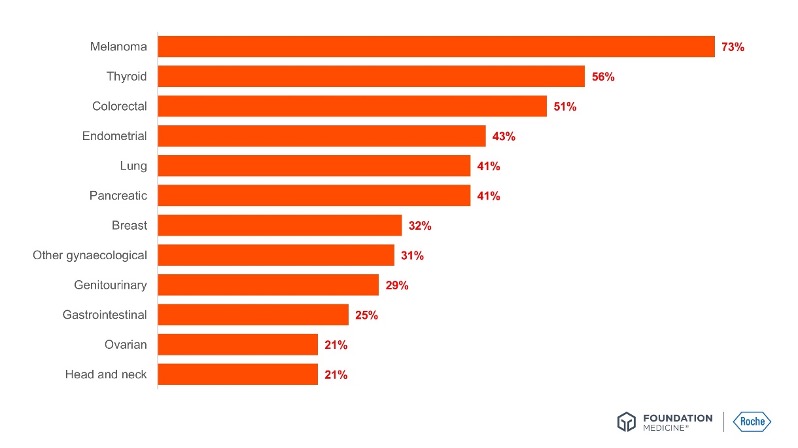

Significant progress has been made on this front in the past decade, making personalised cancer therapy already a reality for some. Today, several types of cancer harbour molecular alterations that can be targeted by precision medicine approaches (Figure 1). With the number of targeted therapies set to grow – there are over 150 different targets currently in development, with more than 700 different compounds targeted at them – many more patients will soon benefit from such novel treatments.

Figure 1: The percentage of patients who tumours were driven by certain genetic mutations that could be targets for specific drugs, by types of canceriii.

There are two prominent drivers that are making precision oncology a wider reality for all patients, namely advancements in genomic profiling, as well as the evolution of regulatory science.

Millions of molecular alterations – one test

There are over 250 types of cancersiv, and 350 genes that contribute to cancer developmentv, but one unique cancer profile. If the goal of precision medicine is to uncover this very individuality, then genomic profiling is playing a fundamental role in making this possible.

Genomic profiling is such a revolution as it allows physicians to test a very small amount of tumour for the many possible molecular alterations that could be targeted with drugs. The effective and reliable matchings of patient to therapy depend on two factors. First, quality – tests that have been approved and clinically validated by regulatory bodies like the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) provide clinicians the greatest assurance of highly reliable analysis results and confidence in the insights generated. The second aspect is time – testing should take place as early as possible, particularly for advanced stage patients, to allow doctors to explore the greatest number of available treatment options before the cancer progresses.

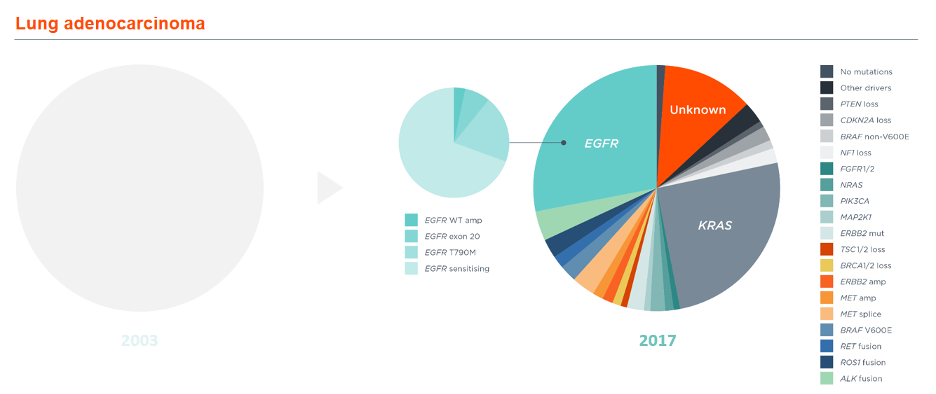

Gene sequencing tests and techniques are driving the personalisation of cancer care, by first helping physicians understand patients’ unique cancer types. Lung cancer is a classic example (Figure 2). Just fifteen years ago, lung cancer was treated as one disease. Since then, the broad classifications of the disease, such as non-small cell lung cancer or small-cell lung cancer have become more and more subdivided as our understanding of the molecular drivers of the disease has improved. We can now divide lung cancer into 15 or 20 different, small subgroups and each of those subgroups can be treated as a fundamentally different disease.

Figure 2: Our evolving understanding of lung cancer and its known genetic alterationsiv.

Beyond improving our understanding of the genetic mutations behind cancers, comprehensive genomic profiling is also delivering new research directions and types of treatments. For instance, determining these biomarkers are crucial to drug development as it increases the odds that a medicine succeeds in clinical trials. One study showed that biomarker-based targeted therapies had a 62% success rate compared to the 11% observed in drugs without a biomarker-targeted indicationvii. Diagnostic tests are used to identify these biomarkers both during research and as companion diagnostics once the successful drugs are approved.

The availability of such tests is key. These tests, like the comprehensive genomic profiling options provided by Roche Foundation Medicine for all solid tumours as well as hematologic malignancies and sarcomas, are being more widely used by oncologists to provide important information to inform treatment options. Using such tests at diagnosis to help determine front-line therapeutic options, instead of at progression or refractory response, may help improve outcomes for patients.

Reimbursement access can also be a barrier. For example, Roche Foundation Medicine has launched Patient Support Programmes in many parts of the world, including Asia Pacific. In the United States, under the national health insurance, which covers certain Roche Foundation Medicine tests for eligible patients, more than 200 million people have access to these broad comprehensive genomic profiling tests to provide them with the most information to fight each individual cancer.

Regulatory science: a balancing act between benefits and risks

Another factor driving precision medicine is the evolution of regulatory science. There is a growing appreciation among regulators that there are new ways to find balances between potential benefits and risks of new medicines to patients.

Taking the US FDA as an example, there are new fast track approvals that will facilitate expedited access to patients for promising therapies and breakthrough therapy designations. These regulations allow for accelerated approvals and priority reviews, all of which allow promising new therapies to reach patients with the appropriate post approval commitments.

In the past three years alone, the US FDA has approved over 25 new drugs including new therapies for monogenetic diseases like cystic fibrosis, and the landmark decision to approve pembrolizumab for all patients whose cancers have a specific molecular alteration called high microsatellite instability (MSI), rather than based on the location in the body where the cancer originated.

We foresee such contemporary regulatory frameworks to set precedence for local authorities globally in the development of their own national guidelines on genomic testing.

All in all, medical innovations in the area of genomic profiling together with a fresh, progressive regulatory approach are pointing to an encouraging future for precision medicine. However, as with every new approach, technology, or product, there is bound to be scepticism in adoption. Collaboration across stakeholders in the healthcare ecosystem is essential to realising the full potential of innovative new technologies that may change the way we identify and treat cancer.

Regulatory science: a balancing act between benefits and risks

Another factor driving precision medicine is the evolution of regulatory science. There is a growing appreciation among regulators that there are new ways to find balances between potential benefits and risks of new medicines to patients.

Taking the US FDA as an example, there are new fast track approvals that will facilitate expedited access to patients for promising therapies and breakthrough therapy designations. These regulations allow for accelerated approvals and priority reviews, all of which allow promising new therapies to reach patients with the appropriate post approval commitments.

In the past three years alone, the US FDA has approved over 25 new drugs including new therapies for monogenetic diseases like cystic fibrosis, and the landmark decision to approve pembrolizumab for all patients whose cancers have a specific molecular alteration called high microsatellite instability (MSI), rather than based on the location in the body where the cancer originated.

We foresee such contemporary regulatory frameworks to set precedence for local authorities globally in the development of their own national guidelines on genomic testing.

All in all, medical innovations in the area of genomic profiling together with a fresh, progressive regulatory approach are pointing to an encouraging future for precision medicine. However, as with every new approach, technology, or product, there is bound to be scepticism in adoption. Collaboration across stakeholders in the healthcare ecosystem is essential to realising the full potential of innovative new technologies that may change the way we identify and treat cancer.

i Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394-424.

ii Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D and Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 2015;136:E359-E386.

iii Tsimberidou AM, Iskander NG, Hong DS, Wheler JJ, Falchook GS, Fu S, Piha-Paul S, Naing A, Janku F, Luthra R, et al. Personalized medicine in a phase I clinical trials program: The MD Anderson Cancer Center initiative. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;15:6373–6383.

iv Armengol G, Ramon Y Cajal S. Funnel Factors. In: Schwab M, editor. Encyclopaedia of Cancer. 2nd ed. New York: 2008.

v Stratton MR, Campbell PJ, Futreal PA. The cancer genome. Nature. 2009;458(7239):719-724.

vi Adapted from Jordan EJ, et al. Cancer Discov 2017;7:596–609.

vii Falconi A, et al. Biomarkers and receptor targeted therapies reduce clinical trial risk in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2014 Feb;9(2):163-9.